Introduction to LDAP¶

When using a single system for your environment, user account and group

membership information can be retained using a local database such as

/etc/passwd (and friends), but for added functionality, such as a global

address book of all users, software applications that are your groupware client

(MUA) need something they can talk to.

Kolab Groupware uses, by default, the Light-weight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), which is a widely adopted, mature Open Standard.

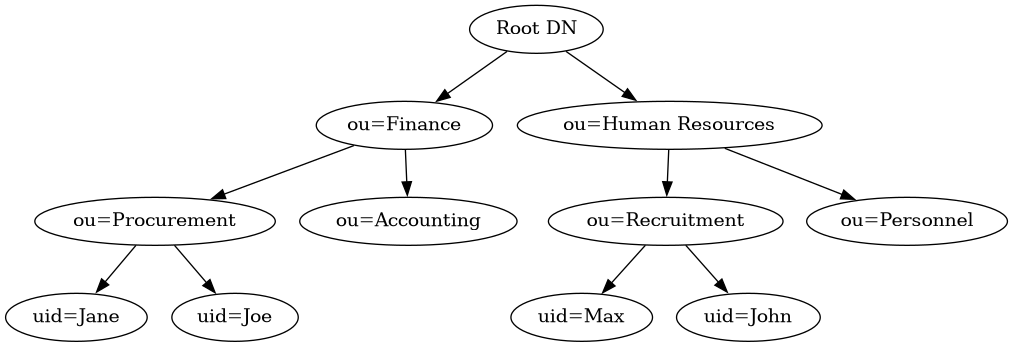

Information about users, groups, and possibly much more, is contained within a hierarchical tree of objects, known as a Directory Information Tree (DIT). In this way, a DIT is built as a tree – starting at the root, branches articulate the structure of the tree, and ultimately hold many leaves.

A DIT is composed of strictly defined objects, each of which has one or more [1] types or classes, and each class may allow one or more attributes to be associated with the object.

Relating back to the example of an actual tree, these types or classes are used to an object represent a branch, leaf, bird, nest, fruit, etc.

A directory information tree is usually represented as follows:

Note

This is an example, and NOT how you should structure your tree.

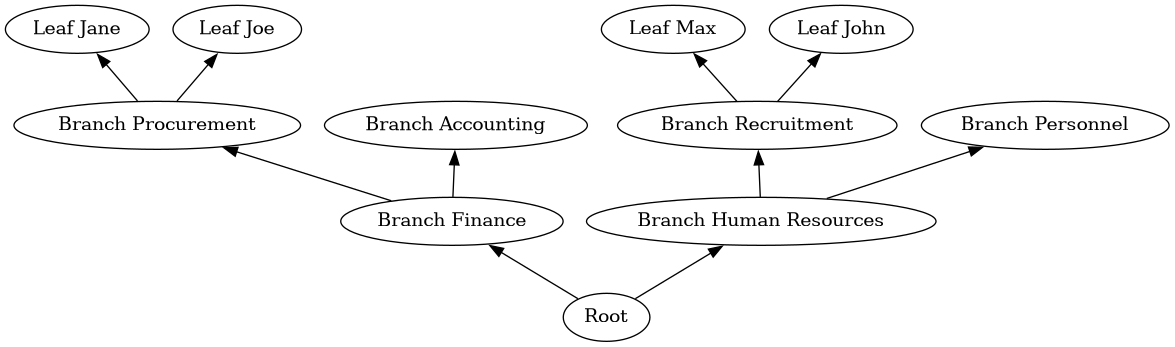

The exact same diagram though, flipped up side down, much better represents an actual tree:

The structuring of a tree is useful for a variety of purposes, some of which may be useful to you, while others are likely not.

A few standard scenarios that could be serviced more optimally when the tree is structured include:

The use of branch offices in different locations,

The use of different departments in an organization,

To prevent access of all (other) users to certain users contained in a branch of the tree, such as mobile phone numbers for board members,

To apply policies to certain individuals, such as implicit mobile synchronization authorization for road warriors,

To delegate authority over a certain branch of the tree, such as an

ou=Contactsbranch for Sales & Marketing department personnel to maintain large sets of contacts.

Distinguished Names and Relativity¶

To uniquely identify an entry, one uses a so-called distinguished name (DN) to essentially describe the location of the object, which must be unique, because not unlike in real life, only one object can be in a given place at a particular time.

For Joe in Procurement for example, such a distinguished name would be:

uid=Joe,ou=Procurement,ou=Finance,Root DN

Like with the tendency to represent a DIT upside down, to establish the path one would use to climb a tree and navigate to a particular leaf, you need to read the components that make up this DN from the right, to the left.

You may have noticed that the names of each component are prefixed with something – such as the branches are prefixed with ou= before we get to their name.

The ou is one of the attributes associated with the object, and is designated the relative DN naming attribute, or “naming attribute” used in establishing the “relative DN” (RDN).

It usually suffices to refer to these attributes as “naming attributes”, as the first value stored in it (if the attribute is or can multi-valued) is used for the RDN, and any other values are considered aliases.

It is worthwhile considering that the RDN tends to be composed of naming attributes that only have values that are considered globally unique (i.e. no two objects with the same attribute set to the same value exist anywhere in the tree), so that a child object can be associated with a different parent object with relative ease.

Suppose, for example, a user John works in Recruitment, and another user John works in Personnel. If the RDNs used for both LDAP entries were uid=John, the one John would collide with the other John, should either John move from the one department to the other department within Human Resources.

The choice of a naming attribute has implications on the values you can use, the configuration of a variety of applications and systems you might use, the administration of your environment and as such are considered to be of on an architectural level, to be taken care of when designing your environment, as changes tend to become prohibitively expensive once implemented in production.

Searching and Listing Objects¶

To seek out a particular object or a list of objects of a particular type, one uses a base dn to search against, a filter to search with, and a scope to determine the depth of nested object levels to descend into, starting from the base dn.

The users, groups and other groupware objects stored in these databases have

email addresses (to enable the exchange of messages), and email addresses have

domain name spaces (the part after the @ in email addresses).

As such, a root dn – the directory tree for an organization – is most commonly associated with at least one domain name space.

Searching and listing operations are executed for a variety of purposes, and in different contexts.

These include, for example:

Navigating an LDAP address book,

Authentication and authorization,

Automatic completion of names and/or addresses (being) specified in a To/Cc/Bcc field of a mail user agent (MUA),

Recipient address resolution, for the delivery of inbound email messages to be delivered to the correct individual mailbox(es),

and many more.

Authentication¶

Authentication against LDAP is done through a so-called bind operation. The LDAP client specifies the bind dn (yes, distinguished name again) and the bind password.

Users, however, tend not to remember the distinguished name of their LDAP entry. The authentication process in individual applications is therefore often assisted within the application.

A POSIX system for example uses, by default, the uid attribute for the

username to be used in authentication, and expects to be able to search for the

specified username (the filter would be

(&(objectclass=posixaccount)(uid=%s))), retrieve the entry DN for the result

found, and perform a bind operation with that DN.

Kolab Groupware applications by default allow the user to login using either of the following:

The

uidattribute value (often something likedoeordoe2for a user John Doe),The

mailattribute value, either fully specified (john.doe@example.org) or the localpart only (john.doe),Any

aliasattribute value, either fully specified (jdoe@example.org) or the localpart only (jdoe).

The filter for such an event would be

(&(objectClass=kolabInetOrgPerson)(|(uid=%U)(mail=%U@%d)(mail=%u)(alias=%U@%d)(alias=%u))),

where:

%d

is the login username domain part, or if not specified, the configured default domain for the application or instance thereof,

%U

is the login username local part,

%u

is the full login username.

This is an extremely liberal authentication filter, and it should be noted that the attribute values should all be globally unique.

Footnotes